The Helium Economy

July 9, 2010

When I first started working as a professional scientist, one of my research areas was

superconductivity; notably, the superconductivity of alloys of the

rare earth elements with

transition metal elements, and with the

hydrides of these alloys. Our work was novel enough to be published in Physical Review Letters.[1] One interesting thing about this research was that it used superconducting magnets, so our superconductivity research was enabled by prior superconductivity research. This happens often in science, where new tools beget new avenues of research.

One thing we needed in abundance was

liquid helium, which has a boiling point of 4.22 K (-268.93

oC). It cooled our magnets, and it cooled our specimens. Our dewars had an outside blanket of

liquid nitrogen (77.36 K) that shielded the helium in the inner chambers from the heat of the outside world. We used a lot of liquid helium, since our magnets were large. Often an experiment would consume 200 liters of liquid helium at a cost of about five dollars per liter. In comparison, liquid nitrogen was just fifty cents a liter. Five dollars a liter has been about the price of liquid helium over the course of the last thirty years, but that's expected to change.[2-3]

Helium is plentiful in the universe, but rare on the Earth. Fortunately, it's concentrated in

natural gas, where it collects as a result of radioactive decay of elements in the Earth's crust. In some natural gas fields in southwest Kansas, the Texas panhandle and Oklahoma, helium concentrations range from from 0.3 - 2.7%. Helium's military importance, first in

barrage balloons, and later in technology products, prompted the US government to separate helium from natural gas streams and store it as a gas in an underground salt dome in what was called the

National Helium Reserve. By the mid-1990s, this reserve, near Amarillo, Texas, held over a billion cubic meters of helium gas worth about $1.4 billion. Congress decided that the US should stop collecting helium and start privatizing the helium economy, so it passed the Helium Privatization Act of 1996. The

US Department of the Interior was directed to deplete the reserve within twenty years.

Of course, this huge supply led to extremely low helium prices in the short term, so a lot of helium is being used when other gases, such as

argon, could suffice. As supplies dwindle, the price is expected to take a huge upturn. This will impact not only niche research areas, such as superconductivity and

Bose-Einstein condensates, but larger technology areas. These include the production and packaging of integrated circuits, welding, and leak detection. Helium is an excellent heat transfer medium for nuclear reactors, since it has the highest thermal conductivity of any gas (20.786 J/mol-K at 25

oC) and an insignificant

neutron cross-section.

NASA uses it to pressurize fuel tanks.

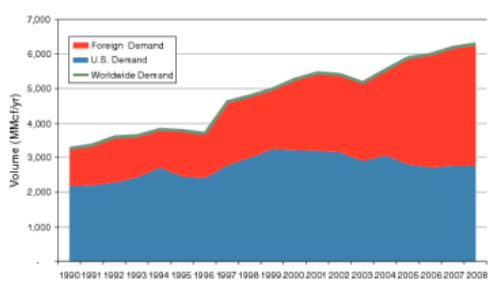

US helium consumption (blue) and other countries (red) from 1990-2008, from Ref. 4.

The US

National Materials Advisory Board and

National Research Council have issued a report [4], "Selling the Nation's Helium Reserve," that recites the many uses of helium and analyzes the impact of the Helium Privatization Act of 1996 on US scientific competitiveness and national security. Among their recommendations are a subsidized price for university research funded by the government, and a requirement that government facilities develop an infrastructure to recycle their helium. A relevant report on natural gas reserves was published also this year.[5-6] Globally, there's an estimated 16,200 Trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of natural gas available. This is 150 times the current annual natural gas consumption. In the US alone, there's an estimated 650 Tcf, with some estimates going as high as 870 Tcf. Even at just a quarter percent concentration, that's a lot of helium.

References:

- P. Duffer, D.M. Gualtieri, and V.U.S. Rao, "Pronounced Isotope Effect in the Superconductivity of HfV2 Containing Hydrogen (Deuterium)," Phys. Rev. Lett. vol. 37, (1976), pp. 1410-1413.

- John Timmer, "Price shocks waiting as US abandons helium business," ArsTechnica, July 5, 2010.

- "Helium Supplies Endangered, Threatening Science And Technology," Science Daily, Jan. 5, 2008.

- Committee on Understanding the Impact of Selling the Helium Reserve of the National Materials Advisory Board and National Research Council, "Selling the Nation's Helium Reserve" (2010).

- Jen Hirsch, "MIT releases major report: The Future of Natural Gas," MIT Press Release, June 25, 2010.

- Ernest J. Moniz and Henry D. Jacoby, Eds., "An Interdisciplinary MIT Study: Future of Natural Gas (Interim Report), Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2010.

Permanent Link to this article