Bacterial Signature

November 12, 2015

Upstate New York, where I spent the early years of my life, is a vast

forest occasionally punctuated by a small

town or

city. The larger cities of Upstate developed along the

Erie Canal, a 584

kilometer waterway that links the

Hudson River at

Albany to

Lake Erie at

Buffalo. The only way such a waterway can function is by a system of

locks that controls the

flow of

water through a

differential elevation of about 172

meters. The canal opened in 1825.

A 1912 engraving of Lock No. 11, at Amsterdam, New York, of the Barge (née Erie) Canal.

(Via Wikimedia Commons.)

The Erie canal was an

innovation and an

engineering marvel at its time. Just as today, when the

automobile has inspired many useful

technologies, waterway transportation did the same in its era.

American engineer,

Robert Fulton (1765-1815), was inspired by the

Watt steam engine of the late

18th century to construct the first commercially successful

steam-powered boat in 1807. I wrote about steam power in a

previous article (Steam Power, January 28, 2011).

This boat, the

Clermont, carried passengers between

New York City and Albany. Although it was a success, it was initially called "Fulton's Folly." This characterization was apt for steam engines of the time, which had a likelihood of

exploding. As recalled in a recent story in the

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette,

Charles Dickens and his

wife were uneasy about steam travel during their 1842 visit to

Pittsburgh, but they were advised that steamboats fitted with a

pressure relief valve were considered safe.[1]

During my

childhood, I lived in

Utica, New York, one of the cities along the Erie Canal. A trip of just a few miles in any direction would lead off into the wilderness. One wilderness adventure for our

family was a trip to the

Catskill Game Farm, which, despite the name, was actually a

zoo. What do I remember most about this zoo? It's the

odor.

It's not the the staff was negligent in its responsibilities. It's just that

bacteria feed from both the input and output streams of

animal life, and there are multiple sources for bacterial infiltration in a zoo, such as

food,

feces, and

urine. Perhaps I exaggerate, but you could turn off your

GPS within a

mile of a zoo and still find your way. This is much more of a problem with

industrial farming, such as

pig and

poultry farms.

An article in

Modern Farmer magazine states that there are more than 200

chemical compounds in

swine odor, which includes such notables as

ammonia,

hydrogen sulfide, and a mixture of

organic compounds that smells like

rotting flesh.[2] Poultry farms emit 60-150 odoriferous compounds, such as "

volatile fatty acids,

mercaptans,

esters,

carbonyls,

aldehydes,

alcohols, ammonia, and

amines."[3]

American Gothic (oil on beaver board, 1930) by Grant Wood (1891-1942)

The number of farms in the US peaked at 7 million in 1935. There are just 1.9 million remaining, but with nearly the same total acreage as at the peak.

(From the Friends of American Art Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Humans are animals, too, and a quick look around a

supermarket or

pharmacy will show that we're very concerned about

our odor. Some odors are beneficial, like the sex-attractant

pheromones,[4] and there are a variety of

perfumes and

colognes that attempt to mimic their attractive properties. For the unpleasant odors, we at first resort to

soap, and then to things like

antiperspirants, and aptly named "deodorants."

Antiperspirants contain chemical compounds, notably

aluminum chlorohydrate, that slow the rate of

perspiration. This has a beneficial effect, since underarm odor comes from bacterial action on

human sweat, with the armpit area being a nice warm environment for bacterial growth. The chemical,

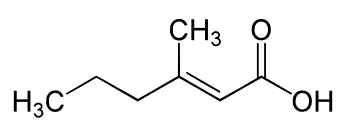

trans-3-Methyl-2-hexenoic acid, is the principal component of body odor.

Trans-3-Methyl-2-hexenoic acid

(Wikimedia Commons image.)

Not all body odor is bad. In fact, there are subtle differences in the scent of a person; and, as shown by

experiment, individuals can be identified by their scent. In one study, 100% of

women tested were able to identify their

newborn babies by scent after an hour or more exposure to the

infants.[5]

While most odors are a second-order effect caused by bacteria, today's

technology makes it possible to analyze small quantities of bacteria themselves. This leads to the possibility that individuals might have a traceable bacterial "signature." That's the idea tested by scientists at the

University of Oregon (Eugene, Oregon) and the

Santa Fe Institute (Santa Fe, New Mexico). They found that occupied spaces have a microbial signature distinct from unoccupied spaces, and that individuals have a personalized microbial

aura.[6-7]

Says lead author,

James F. Meadow, who conducted this research while a

postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oregon,

"We expected that we would be able to detect the human microbiome in the air around a person, but we were surprised to find that we could identify most of the occupants just by sampling their microbial cloud."[7]

Bacteria associated with individuals are

dispersed into the

environment through direct contact and by

bioaerosol particle emission from

breath,

clothes,

skin and

hair.[6] Humans shed about a million particles of size less than 0.5

micrometer every hour, many of which would contain bacteria.[6]

In their experiments, the University of Oregon researchers sampled microbes from the air space of a single person sitting in a

sanitized environmental chamber, and they compared that to air sampled in an adjacent, identical, unoccupied chamber.[6] They used high-throughput

DNA sequencing methods to characterize the airborne bacteria.[6] In subsequent, higher resolution, experiments they sampled 8 different people for 90 min each with air flowing through a

collection filter at on and three air change per hour.[6]

Individuals could be distinguished through their airborne emissions in the chamber within 1.5-4 hours.[6] They authors comment that their experiments might help to understand the mechanisms involved in

infectious disease transmission in buildings.[7] At this point, considerable time is involved in detection, but there might be potential

forensic applications.[7] Perhaps the

surveillance society might be worse than we imagined.

References:

- Len Barcousky, "Eyewitness 1842: Dickens finds Pittsburgh full of smoke and fires," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 30, 2015.

- Christopher Weber, "Stink Wars: When a Foul Wind Wafts From a Farm, Is it a Problem?" Modern Farmer, January 27, 2014.

- John P. Chastain, "Odor Control From Poultry Facilities," Chapter 9 of Poultry Training Manual, Clemson Cooperative Extension.

- Napoleon supposedly wrote in a letter to Josephine, Ne te lave pas. Je reviens. (Don't bathe. I'm coming home.)

- M. Kaitz, A. Good, A. M. Rokem, and A. I. Eidelman, "Mothers' recognition of their newborns by olfactory cues," Developmental Psychobiology, vol. 20, no. 6 (November, 1987), pp. 587-591.

- James F. Meadow, Adam E. Altrichter, Ashley C. Bateman, Jason Stenson, GZ Brown, Jessica L. Green, Brendan, and J.M. Bohannan, "Humans differ in their personal microbial cloud," Peerj, vol. 3, Document No. e1258 (September 22, 2015), DOI: 10.7717/peerj.1258.

- New research finds that people emit their own personal microbial cloud, Peerj PressRelease, September 22, 2015.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Upstate New York; forest; town; city; Erie Canal; kilometer; waterway; Hudson River; Albany, New York; Lake Erie; Buffalo, New York; lock (water transport); flow; water; differential elevation; meter; Amsterdam, New York; New York State Canal System; Barge Canal; Wikimedia Commons; innovation; engineering; automobile; technology; technologies; American; engineer; Robert Fulton (1765-1815); Watt steam engine; 18th century; steamboat; steam-powered boat; Clermont; New York City; explosion; exploding; Pittsburgh Post-Gazette; Charles Dickens; wife; Pittsburgh; pressure relief valve; childhood; Utica, New York; family; Catskill Game Farm; zoo; odor; bacteria; animal; food; feces; urine; Global Positioning System; GPS; mile; intensive farming; industrial farming; pig; poultry; Modern Farmer magazine; chemical compound; domestic pig; swine; ammonia; hydrogen sulfide; organic compound; decomposition; rotting flesh; volatile organic compound; fatty acid; thiol; mercaptan; ester; carbonyl; aldehyde; alcohol; amine; oil paint; beaver board; Grant Wood (1891-1942); acreage; Art Institute of Chicago; human; supermarket; pharmacy; body odor; pheromone; perfume; cologne; soap; deodorant; antiperspirant; aluminum chlorohydrate; perspiration; human sweat; trans-3-Methyl-2-hexenoic acid; experiment; woman; newborn baby; infant; University of Oregon (Eugene, Oregon); Santa Fe Institute (Santa Fe, New Mexico); aura; James F. Meadow; postdoctoral research; dispersion; disperse; environment; bioaerosol; breathing; breath; clothing; clothes; skin; hair; micrometer; disinfectant; sanitize; environmental chamber; DNA sequencing; air filter; collection filter; infection; infectious disease; epidemiology; transmission; forensic; surveillance society.