Lingua Franca

November 10, 2014

At one time,

universities had a

language requirement for the

Ph.D. degree.

Doctoral candidates needed to pass an

examination to demonstrate their understanding of a

foreign language. My

thesis advisor took the

French language exam, which was the same for everyone no matter what their

profession. He said it was hard, but he passed.

By the time of completion of my degree, such an exam was not required, at least at my university. If the requirement had still been in place, I wonder whether I could have been tested in

Latin, the language with which I am most familiar after

English.

Latin was the language of most

scholarship until a few hundred years ago. Latin, a vestige of the vast

Roman Empire, was the universal language for the first seventeen

centuries AD. All

books were written, actually

hand-written until late in the

fifteenth century, in Latin, and it was the language of the

church. When

Johannes Gutenberg published his first book using

movable type,

that book was a

Latin Bible.

The

scientific revolution was chronicled in such important Latin texts as

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543) by

Nicolaus Copernicus, which offered his alternative model to

Ptolemy's geocentric system;

Sidereus Nuncius (1610), in which

Galileo, who was also the first prominent scientist to publish in his native language, reported on his observations with a

telescope; and

Isaac Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687). The prolific

Swiss mathematician,

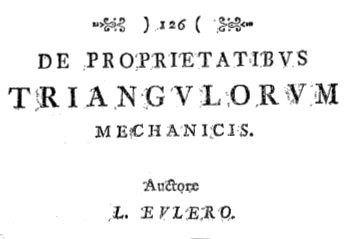

Leonhard Euler (1707-1783), published in both Latin and French (see figure).

Title portion of Euler's 1783 paper, "De proprietatibus triangulorum mechanicis (On the properties of triangles in mechanics)."[1]

(Dartmouth University Euler Archive.)

The

19th century trend was towards using your

vernacular for

scientific publication, so French, English, and

German journals were published, and many

scientists published in multiple languages.

Charles Darwin published his books, such as the famous

On the Origin of Species (1859) in English.

Chemistry had always been associated with the German language, and much early

physics was published in German, as well. In my student days I frequently consulted a series of

reference books called "

Strukturbericht," published as a supplement to the German journal,

Zeitschrift für Kristallographie.

In the Early part of the

20th century, German was poised to become the principal scientific language, and not merely because your entire scientific paper could be written as a single word. I exaggerate, but such German words as

Bremsstrahlung, "braking radiation," contain an entire idea in a single word. Many scientific luminaries of the early 20th century, such as

J. Robert Oppenheimer and

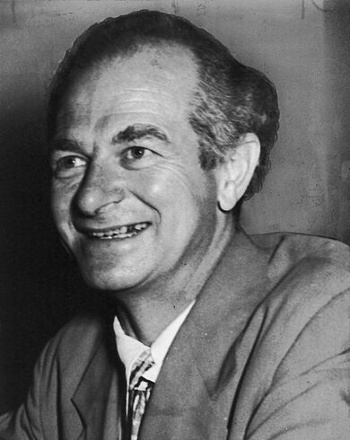

Linus Pauling, studied in Germany early in their careers.

Linus Pauling (1901-1994) in a circa 1954 photograph.

As the recipient of a 1926 Guggenheim Fellowship, Pauling studied under German physicist, Arnold Sommerfeld, in Munich, Germany. He also studied under physicists, Niels Bohr in Copenhagen, and Erwin Schrödinger in Zürich.

(United States Library of Congress, reproduction Number LC-USZ62-76925, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Today, English is the preferred language of science, a

lingua franca. As discussed in a forthcoming book, "

Scientific Babel,"[2] by

Michael Gordin, a

professor of the

history of science at

Princeton University, the rise of English and decline of German as the language of science came about not merely because of the

hegemony of

American science after

World War II, but also because of a backlash against the German politics that resulted in two world wars within a half

century.

As a current example of how much English is a part of mainstream science, the

Norwegian husband and wife neuroscientists who were awarded this year's

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine,

Edvard Moser and

May-Britt Moser, published their work in English.[4] Gordin writes that the ascendancy of English is essentially the result of the collapse of German as the language of scientific discourse

World War I launched the first wave of German scientific isolation, as

Belgian,

French and

British scientists boycotted German and

Austrian scientists. Scientific practice became demarcated into two camps, with the Germans and Austrians in one, and the rest of the scientific world, speaking mostly English and French, in the other. This was also the time when some important international scientific organizations, such as the

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, were founded, and these did their business in English or French.[4]

The

United States entered World War I in 1917; and, says Gordin, anti-German

hysteria swept the country. Although many in the US spoke German as their first language, in such states as

Ohio,

Wisconsin and

Minnesota, the German language was criminalized in 23

states. Speaking German in public or on the

radio, and

teaching it to

children was

criminalized. Such

laws were declared

unconstitutional by the

US Supreme Court in 1923, but the damage had already been done.[4] The result was a generation of scientists who spoke English, only.[4]

Following World War II, the American scientific enterprise dominated the world, and much important research was published in English. The rest of the world needed to learn English to catch up, and they needed to write in English to get noticed. It's, therefore, no surprise that the Norwegian Nobel Prize winners published in English. We shouldn't be surprised that Gordin's book, which runs to 424 scholarly pages, is written in English.[2]

English has spread through the world largely through the influence of American films and music. More than half the songs on one Internet radio station from the Netherlands (Radio 8 FM) to which I occasionally listen, are in English.

I've never seen "Lobster Man from Mars," but its summary on the Internet Movie Database[6] makes it look interesting.

(Via Wikimedia Commons.)

![]()

References:

- Leonhard Euler, "De proprietatibus triangulorum mechanicis (On the properties of triangles in mechanics, Eneström Number E536)," Acta Academiae Scientarum Imperialis Petropolitinae 1779, 1783, pp. 126-155.

- Michael D. Gordin, "Scientific Babel - How Science Was Done Before and After Global English," To Be Published (April, 2015), University of Chicago Press, 424 pp., ISBN: 978-0226000299. Listed on Amazon.

- Michael D. Gordin, "Scientific Babel: The Problem of Minor Languages in the History of Modern Science," 2009 Presentation, Princeton University Web Site (PDF File).

- How did English become the language of science? -The World in Words, Nina Porzucki, Producer, Public Radio International, (October 6, 2014).

- Podcast of ref. 4.

- Lobster Man from Mars (1989, Stanley Sheff, Director) on the Internet Movie Database.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: University; language; Doctor of Philosophy; Ph.D. degree; assessment test; examination; foreign language; doctoral advisor; thesis advisor; French language; profession; Latin; English; scholarly method; scholarship; Roman Empire; century; Anno Domini; AD; book; manuscript; hand-written; 15th century; fifteenth century; Catholic Church; Johannes Gutenberg; movable type; Gutenberg Bible; Vulgate; Latin Bible; scientific revolution; De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543); Nicolaus Copernicus; Ptolemy; Almagest; geocentric system; Sidereus Nuncius (1610); Galileo Galilei; telescope; Isaac Newton; Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687); Switzerland; Swiss; mathematician; Leonhard Euler (1707-1783); triangle; classical mechanics; Dartmouth University Euler Archive; 19th century; vernacular; scientific literature; scientific publication; German language; scientific journal; scientist; Charles Darwin; On the Origin of Species (1859); Chemistry; physics; reference work; reference book; Strukturbericht; Zeitschrift für Kristallographie; 20th century; Bremsstrahlung; J. Robert Oppenheimer; Linus Pauling; Guggenheim Fellowship; Arnold Sommerfeld; Munich, Germany; Niels Bohr; Copenhagen; Erwin Schrödinger; Zürich; United States Library of Congress; Wikimedia Commons; lingua franca; Scientific Babel; Michael Gordin; professor; history of science; Princeton University; hegemony; American; World War II; century; Norway; Norwegian; spouse; husband and wife; neuroscientist; Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine; Edvard Moser; May-Britt Moser; World War I; Belgium; Belgian; France; French; Britain; British; Austria; Austrian; International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry; United States; hysteria; Ohio; Wisconsin; Minnesota; U.S. state; radio; education; teaching; child; children; criminalization; criminalized; law; constitutionality; unconstitutional; Supreme Court of the United States; US Supreme Court; film; popular music; Internet radio station; Netherlands; Radio 8 FM; Lobster Man from Mars; Internet Movie Database.