Molybdenum Disulfide for DNA Sequencing

August 27, 2014

Electronics and

computing technology have had a big impact on many

scientific fields. In

biotechnology, this is especially apparent in the

sequencing of DNA. I wrote about advances in DNA sequencing technology in two previous articles (

Full Genome Sequencing, June 7, 2012, and

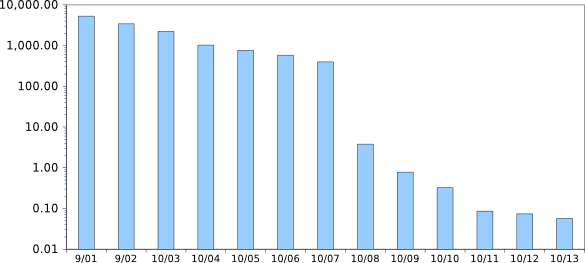

DNA Analysis, September 17, 2010). The cost reduction, as can be seen in the chart, has been huge, and it's been the result of moving DNA analysis from

chemistry to

physics.[1]

Time variation of the cost per megabase of DNA sequencing in US dollars (note the logarithmic scale). The present cost is about five cents, which puts the cost of an entire human genome sequence at about $5,000. In September, 2001, the cost was a factor of 100,000 greater, but the cost has not declined in the last two years. (Graphed using Gnumeric from data at http://www.genome.gov/sequencingcosts.)

The newer,

non-chemical techniques for DNA sequencing are based on the

conductivity change when DNA is threaded through a

nanopore. Passage of a DNA molecule through the nanopore results in a small fluctuation in

electrical current in the

ionic solution in which it's

dissolved. The four different bases,

Adenine (A),

Cytosine (C),

Guanine (G) and

Thymine (T), give different currents since they are slightly different in shape and size.

Graphene sheets have been proposed as a nanopore material, since the thinness of graphene allows good resolution of these base units.[2-4] The use of graphene as a nanopore membrane is an advance over

nanopore sequencing work done in the last

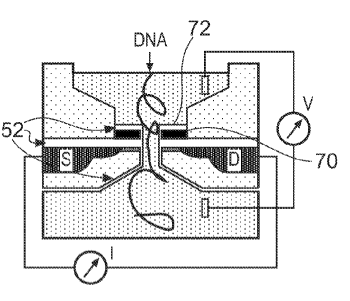

decade.[5] In the example shown in the figure, below, from a recent

US patent, DNA is threaded through a nanopore in the

gate of a

field effect transistor.[6]

Figure one of US patent no. 8,074,827, "Apparatus And Method For Molecule Detection Using Nanopores," by Matthias Merz, Youri V. Ponomarev and Gilberto Curatola (March 11, 2014).

(Via Google Patents))

Graphene, which is an

atomically-thin sheet of

graphite, is highly

conducting in its

plane, but it

insulates the regions on opposite sides of the sheet. A

nanometer hole can be drilled in a graphene sheet using an

electron beam, and the sheet can be used to separate solutions on opposite sides of the sheet. Although this is like the

geometry of a

Coulter counter,[7] the electrical conduction mechanism is different. Solution ions in the hole affect the sheet conductivity of the graphene, and DNA threaded through the holes displaces these ions to change the sheet conductivity.

Mechanical engineers at the

Department of Mechanical Science and Engineering of the

University of Illinois have done

computer simulations on the use of

molybdenum disulfide (

MoS2), a sheet material somewhat like graphene, as a nanopore material for DNA sequencing.[8-10]. Molybdenum disulfide sheets are thin, like graphene. While DNA tends to stick to graphene, introducing

signal noise, DNA does not stick to molybdenum disulfide, so it threads through nanopores cleanly and quickly.[9-10]

While the signal-to-noise ratio for the

ion current of graphene in DNA sequencing is just three, computer simulation found that the signal-to-noise ratio of molybdenum disulfide can be greater than fifteen.[8] Single layers of molybdenum disulfide also offer a different means of base

detection, since the bases also impart a difference in

transverse tunneling current.[8] The nanopores can be crafted to give different edges containing a different combination of

molybdenum and

sulfur atoms to give an optimized signal strength.[8]

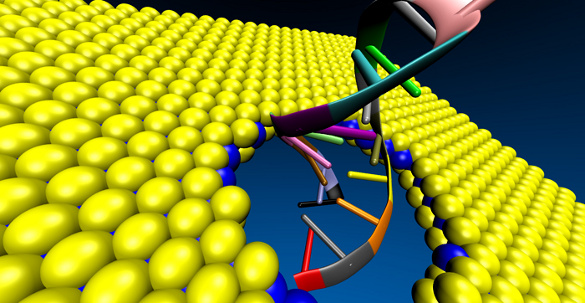

A DNA molecule passing through a molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) sheet. MoS2 has been found to be a better material than graphene for DNA sequencing. (University of Illinois image courtesy of Amir Barati Farimani.)

The computer simulations showed that four distinct signals are obtained from the four different bases in a double-stranded DNA molecule, while other systems have a problem distinguishing A from T and C from G. The University of Illinois research team is now investigating combinations of molybdenum disulfide with another material to produce a workable device.[9] Says

graduate student Amir Barati Farimani, who was the first

author of the

paper describing this

research,

"The ultimate goal of this research is to make some kind of home-based or personal DNA sequencing device... We are on the path to get there, by finding the technologies that can quickly, cheaply and accurately identify the human genome. Having a map of your DNA can help to prevent or detect diseases in the earliest stages of development."[9]

This research was funded by the

US Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the

US National Science Foundation.[9]

References:

- E.R. Mardis, "A decade's perspective on DNA sequencing technology," Nature, vol. 470, no.7333 (February 10, 2011), pp. 198-203.

- Michael Patrick Rutter, "Graphene may hold key to speeding up DNA sequencing," Harvard University Press Release, September 9, 2010.

- Hagan Bayley, "DNA sequencing: enter the graphene nanopore," Nature, vol. 467, no. 7312 (September 9, 2010), p. 164.

- S. Garaj, W. Hubbard, A. Reina, J. Kong, D. Branton and J. A. Golovchenko, "Graphene as a subnanometre trans-electrode membrane," Nature, vol. 467, no. 7312 (September 9, 2010), pp. 190-193.

- Amit Meller, Lucas Nivon, Eric Brandin, Jene Golovchenko, and Daniel Branton, "Rapid nanopore discrimination between single polynucleotide molecules," Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 97, no. 3 (February 1, 2000), pp. 1079-1084.

- Matthias Merz, Youri V. Ponomarev and Gilberto Curatola, "Apparatus And Method For Molecule Detection Using Nanopores," US patent no. 8,074,827, March 11, 2014.

- Wallace H. Coulter, "Means For Counting Particles Suspended In A Fluid," US patent No. 2,656,508, October 20, 1953.

- Amir Barati Farimani, Kyoungmin Min, and Narayana R. Aluru, "DNA Base Detection Using a Single-Layer MoS2," ACS Nano, Article ASAP, July 9, 2014, DOI: 10.1021/nn5029295.

- Liz Ahlberg, "New material could enhance fast and accurate DNA sequencing," University of Illinois Press Release, August 13, 2014.

- Narayana Aluru, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, "Nanopore: MoS2 vs graphene," YouTube video, August 12, 2014.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Electronics; computing; technology; science; scientific; biotechnology; DNA sequencing; sequencing of DNA; chemistry; physics; nucleobase; megabase; United States dollar; logarithmic scale; human genome sequence; Gnumeric; http://www.genome.gov/sequencingcosts; non-chemical; electrical conductivity; nanopore; electric current; electrical current; ion; ionic; aqueous solution; solvation; dissolve; Adenine; Cytosine; Guanine; Thymine; graphene; nanopore sequencing; decade; US patent; field-effect transistor gate; field effect transistor; Google Patents; atom; atomically; graphite; conducting; plane; insulator; insulate; nanometer; electron beam lithography; geometry; Coulter counter; Department of Mechanical Science and Engineering; University of Illinois; computer simulation; molybdenum disulfide; molybdenum; Mo; sulfur; S; signal noise; ion current; sensor; detector; transverse; tunneling current; graduate student; Amir Barati Farimani; author; academic publishing; paper; research; US Air Force Office of Scientific Research; US National Science Foundation; Matthias Merz, Youri V. Ponomarev and Gilberto Curatola, "Apparatus And Method For Molecule Detection Using Nanopores," US patent no. 8,074,827, March 11, 2014; Wallace H. Coulter, "Means For Counting Particles Suspended In A Fluid," US patent No. 2,656,508, October 20, 1953.